Where early missionaries got it wrong

Using local music is a powerful tool for communicating the Gospel, writes ethnomusicologist Rob Baker. Thankfully, African forms of worship are increasing year by year, and the church continues to grow and thrive

Dogon Country: a fascinating, dramatic and culturally rich part of West Africa, whose inhabitants have survived for centuries on the edge of a stark, sheer clifftop 100 miles long. They are experts in understanding the night sky, grow onions in the shallowest of soils, and occasionally walk on stilts. Christianity is one of the main faiths here, along with Islam and African traditional religion. Both Catholic and Protestant missionaries worked amongst the Dogon from the 19th century onwards; as a result, churches sprang up in villages along the cliff and across the plain below.

Dogon Country: a fascinating, dramatic and culturally rich part of West Africa, whose inhabitants have survived for centuries on the edge of a stark, sheer clifftop 100 miles long. They are experts in understanding the night sky, grow onions in the shallowest of soils, and occasionally walk on stilts. Christianity is one of the main faiths here, along with Islam and African traditional religion. Both Catholic and Protestant missionaries worked amongst the Dogon from the 19th century onwards; as a result, churches sprang up in villages along the cliff and across the plain below.

A few years ago, I had the privilege of visiting Dogon Country as a missionary and ethnomusicologist with Wycliffe Bible Translators. One of my major discoveries was the extent to which the early missionaries got it wrong. Rather than promoting indigenous music in worship, they introduced European or American hymns, whose melodies, rhythms and themes were distinctly foreign to the Dogon. One older Christian I interviewed said this:

“Our Dogon instruments were forbidden by the missionaries. ‘It’s for pagans’ they told us. No clapping or dancing was allowed: we just had to stand still, face the front of the church and sing your white songs.”

Given the vibrancy and spontaneity of Dogon music, with its polyrhythmic drum patterns, infectious dances and exciting ‘call and response’ singing style, this would have been a huge and almost insurmountable obstacle for them. And a single Dogon song can easily last 20 minutes, sometimes over an hour. My interviewee continued:

“The tunes were difficult. They would sing just five verses, then suddenly stop and sit down.”

Contrary to popular belief, music is not a universal language; it is a universal phenomenon, but differs in every culture of the world. The choice of scale, the number of beats in a bar, who sings and when, and the instruments used are just a few of the elements which vary from culture to culture. And so, we cannot simply transplant the music of one culture into another and expect it to work; it would be like taking a Big Mac and fries to a remote Amazonian tribe: they would not know how to hold it, how to eat it, or even what it was.

From the second half of the 20th century, African churches began to gain greater autonomy, and consequently introduced their own instruments and styles of music. The results have been stunning, as genuinely local artforms are used to worship God; songs from the heart of the people, which have significance for the people, and in a musical language which makes sense to them.

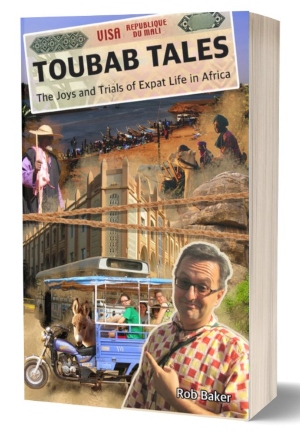

But there’s still a long way to go, as the legacy of Western culture lingers on even today. My latest book, Toubab Tales devotes three chapters to the Dogon, including a visit I made to a Dogon church one Sunday; it was an encouraging, but somewhat disappointing experience:

“The service starts only fifteen minutes late, and worship begins with three very Western songs, one of which I instantly recognize as Amazing Grace. The fourth song sounds much more African and uses a vaguely pentatonic scale with call and response. Two further semi-Dogon songs follow, all accompanied by the gomboï talking drum, a gourd shaker (always played by women), and square drum, introduced in the 1960s. It’s encouraging to see these instruments, but the church still bears a massive imprint of Western missionaries and has become a hybrid of two cultures, rather than being genuinely Dogon. There’s no dancing or moving about to the songs, just people standing still in straight rows.”

Following this experience, I ran a song-writing workshop with the Dogon, in preparation for the dedication of the newly translated Dogon bible. After a few days of teaching, composing and refining, the new songs were ready. In a narrow gully on the clifftop, I set up my microphones and mixing desk under a mango tree, and we recorded each song. There was great joy on everyone’s faces, as they worshipped in a culturally relevant way, using local drums and song styles, as well as clapping and dancing. The song words were inspiring, giving thanks for the Word of God in the Dogon language, and using imagery and themes pertinent to Dogon culture.

Following this experience, I ran a song-writing workshop with the Dogon, in preparation for the dedication of the newly translated Dogon bible. After a few days of teaching, composing and refining, the new songs were ready. In a narrow gully on the clifftop, I set up my microphones and mixing desk under a mango tree, and we recorded each song. There was great joy on everyone’s faces, as they worshipped in a culturally relevant way, using local drums and song styles, as well as clapping and dancing. The song words were inspiring, giving thanks for the Word of God in the Dogon language, and using imagery and themes pertinent to Dogon culture.

The day after this recording session, several Dogon men arrived at the house of the local pastor. They were not Christians, but had heard the music and were intrigued:

“We heard your Dogon songs of worship yesterday. We’d like copies of the music, as it was pleasing to our ears.”

Using local music is a powerful tool for communicating the Gospel; one early missionaries were slow to utilise. Now, thankfully, African forms of worship are increasing year by year, and the church continues to grow and thrive.

Rob Baker is an author and ethnomusicologist. His new book Toubab Tales is available on Amazon and The Book Depository across the world. Rob is a member of Ampthill Baptist Church

Rob Baker is an author and ethnomusicologist. His new book Toubab Tales is available on Amazon and The Book Depository across the world. Rob is a member of Ampthill Baptist Church

Baptist Times, 15/09/2020