The voice of Disney, and another voice

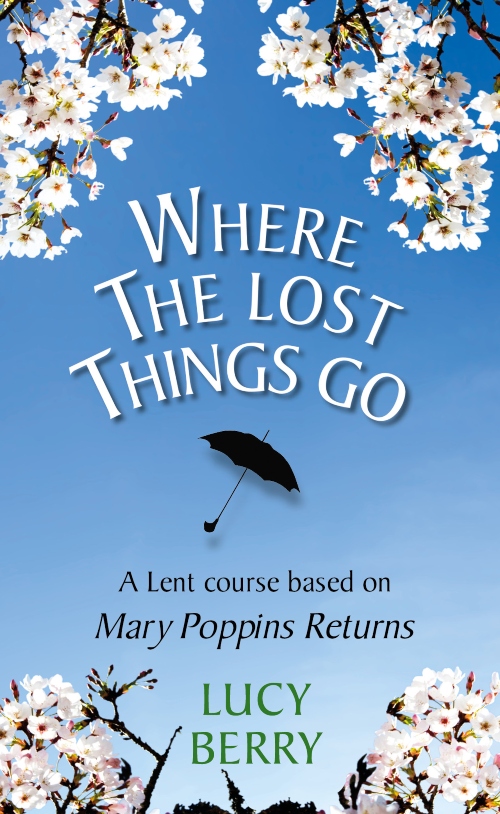

What can Mary Poppins teach us about Lent? A surprising amount, says author Lucy Berry, whose new Lent group study guide is based on the 2018 Oscar nominated movie

I was astonished to be asked to write a Lent course on Mary Poppins Returns. I said yes; even though I had no notion of whether I could. But I’m someone who goes looking for the hidden God in anything and everything. I believe God lurks particularly where uninvited. So I gave it a go.

I was astonished to be asked to write a Lent course on Mary Poppins Returns. I said yes; even though I had no notion of whether I could. But I’m someone who goes looking for the hidden God in anything and everything. I believe God lurks particularly where uninvited. So I gave it a go.

Disney films are funny old things. they’re a bit cheesy and a bit corny, but they sometimes sneak up under our defences and makes us a bit weepy. It’s a comforting kind of weepy though isn’t it? Weepy films are sort-of comforting. That ability to be lightweight and, at the same time, cosily wistful is really quite clever. And Disney is really very clever.

There is a chirpy, brave, optimistic voice threading its way through Disney films, which the Disney Corporation strives to keep alive. It chirrups along, requiring us to identify, to keep our peckers up, to let our conscience be our guide. It is the unalterable Voice of Walt Disney himself, speaking through every Disney film. And it sounds like a million dollars.

As a child, I identified with Dumbo, Bambi, (and the nothing-like-Kipling’s Mowgli), in ways that the Voice intended me to. The little slivers of anxiety in Disney films are always followed by dollops of jollity; for ultimate intention is cosy relief. Disney never quite confronts, so it can’t quite do salvation...so it pretends. I couldn’t know that I was being fed sentiment, not emotion.

Looking back at them now, those films do contain truisms which, (had my mother’s anchor not been the Bible), would have seemed entirely true to me. But truisms aren’t true enough. I knew, even then, that when you wish upon a star, your dreams do not come true.

Before I could start writing about Mary Poppins Returns I went back and read the books. As my little son was growing up, I used to sit with him, reading or watching stories. Writers can’t easily keep their ideas of world-order out of their stories; so, to avoid boredom (we watched Wind in the Willows twenty-seven times), I started looking for where God came in. God, for Pooh and Piglet, is Christopher Robin: a Person who knows more than everyone else, but has more to learn. God, for Thomas the Tank Engine, is the Fat Controller: the Person in charge of everything. God, for the Railway Children, is Father: a wronged Person returning from great suffering, bringing a new earth.

Have you read all the Mary Poppins books? I often read them as a child, and then I read them all again for this project. They are fun enough to have caught Walt’s eye. But the author, P. L. Travers, deals with ideas and issues which Disney has seldom raised since Pinnochio; ideas about selfishness and integrity. Some Poppins stories have narratives which punish. If Poppins equates to God for P.L. Travers, then she is complex Person bringing both joy, confusion laced with shame, and an opaque determination not to explain. Whether you like Mary or not, Poppins books are all-of-a-piece, and they are sincere.

Mary Poppins, mediated through Disney, is something else. In neither film is she the whole person whom we find in the books. But then it is rare for Disney characters to find their own voice. The Disney Voice is too strong for them; not insincere exactly, but usually too eager-to-please to be authentic.

The Bible is not eager to please, or easy to please. It is absolutely and concretely sincere. It is about things which the writers believe are not be negotiated. It is demanding; and so Lent is necessarily very hard. Year on year, the story of Christ’s time in the wilderness requires change, choices and decisions from us. It is about all kinds of hunger, and power, and the temptations of the ego. It leads us up to a horribly shocking story which cannot be negotiated, and must be faced. Lent and Easter are, supposedly, the antithesis of Disney.

But watch Mary Poppins Returns, and you will see big themes opening, (hunger, power, money, death, loss, light), which occasionally overwhelm the traditional Disney Voice and leave it struggling: This film is not completely Mickey Mouse. The plot is not so cosy. It somehow broke the mould. There is one character in the film, (I won’t say which), who loves unconditionally, and risks everything for other people. There is one character who is being crucified. And there is one song, (I won’t say which), which reflects life, love, doubt and loss with touching accuracy.

If you do watch the film and work through the Lent course, I’d ask that you watch closely. Nothing works in this film the way a Disney film ‘should’. Look carefully and you’ll see that it doesn’t quite end up where it is destined. You see, I think God got in, uninvited. If you listen carefully, you will hear Disney’s Voice falter from time to time, as the still small voice steps in.

Lucy Berry is a performance poet and a United Reformed Church Minister. She is a fifth generation Londoner and part of a mixed-heritage family. For four years, Lucy was Poet in Residence for Radio 2’s Jeremy Vine Show. She has worked in advertising, in HMP Holloway, and as an art therapist.

Her work constantly explores what Bible stories are telling us about our successes, our denials and our terror of change. She was until recently the Joint Public Issues Team poet-in-residence

Do you have a view? Share your thoughts via our letters' page.

Baptist Times, 14/02/2020