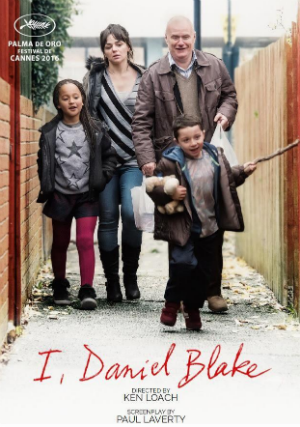

Review: I, Daniel Blake

The harrowing reality of UK poverty is highlighted in Ken Loach's new film I, Daniel Blake - and every church should organise a visit to see it, writes Jon Kuhrt

In 1967, Ken Loach’s film Cathy Come Home was a seminal moment in the national consciousness about homelessness. The film led directly to the formation of the national housing charity Shelter.

In 1967, Ken Loach’s film Cathy Come Home was a seminal moment in the national consciousness about homelessness. The film led directly to the formation of the national housing charity Shelter.

I, Daniel Blake is a Cathy Come Home for our times. Loach has once again shone an unflinching spotlight on poverty in the UK today. It's a film for the zero hours contract, austerity, food bank, benefit-sanction era we are currently living in.

Gritty reality

Daniel Blake has the jagged edges of all Ken Loach films, with abrupt fade-outs between scenes and and extras who act like they have been plucked raw from the community. Thus gritty reality is embedded in the very texture of the film.

Many films rely on the extraordinary. Poverty and hardship is often just a backdrop, a context from which incredible individuals escape, move on and find their dreams. These Hollywood narratives can be inspiring and powerful. But they rarely reflect reality.

In contrast Daniel Blake is a deeply ordinary story. It lays bare the monotony, anger and frustration created by poverty and dealing with welfare bureaucracy. And from my experience of the council estates I have lived in, and the homeless hostels and community centres I have worked at, the characters are convincing and their situations ring true. Daniel is a middle-aged carpenter who has lost his wife to illness and has had a recent heart attack which has meant he has had to stop working. At the Job Centre Plus, he bumps into Katie, a single mum who has just moved into the area.

Convincing

I lived in a block of flats in Kings Cross very similar to where Daniel Blake lives. My neighbours were people quite similar to the characters depicted – by and large decent people struggling in different ways to bring up their kids right, make ends meet and to look out for each other.

The situations conveyed in the film also resonate with conversations I have with homeless people coming into the West London Mission. Michael, the rough sleeper staying at our winter shelter who I wrote about recently, told me about how his computer-phobia and mental health problems caused him to walk out of a government course that he had been told to complete. This in turn led to his housing benefit being cut, being evicted from his flat and becoming homeless on the street.

Ken Loach is not making this stuff up. I, Daniel Blake may be a fictional story but it's one that reflects reality.

Faces of poverty

The film reinforced my view that deprivation in the UK is complex fusion of different forms of poverty.

Primarily, Daniel and Katie both face serious material poverty due to their circumstances. These challenges are compounded by the chronic bureaucracy of the welfare system.

Katie’s failed relationships with her two children’s fathers are intrinsic to the challenges she faces. And her homelessness has meant being relocated 300 miles from her wider family. Relational poverty deepens and compounds her vulnerability.

And both forms of poverty are continually undermining both Daniel and Katie’s dignity, self-worth and sense of identity. Daniel comes out fighting, vowing right to the last never to give in. Katie confesses that she is ‘going under’ and feels she has no option but to turn to activities which further undermine her self-esteem.

Faith fighting poverty

We live in a time when welfare reform and the numbers using food banks is front page news. The compassion showed by many churches and community groups in setting up food banks is building up into a concern for justice. This is right. We should not just be pulling people out of the river; we should also go upstream and prevent them from being pushed in in the first place.

I firmly believe that the Church has resources to combat all three of these forms of poverty:

-

To fight material poverty through practical help such as food banks and by advocating for social justice.

-

To fight relational poverty by being a diverse, welcoming community supporting families and especially those who are vulnerable and lonely.

-

And most deeply, to fight a poverty of identity by sharing a gospel message of God’s love, forgiveness and affirmation which is available to everybody.

Your response?

I would recommend that every church should organise a trip to go and see the film and then discuss how they can respond to the Daniel Blakes and Katies who live in our communities. Why not organise this in your church and announce it this Sunday?

One action to start the ball rolling could be to sign up to Church Action on Poverty‘s End Hunger in the UK campaign. This would be a fitting response to this powerful film.

Jon Kuhrt works at the West London Mission as Executive Director of Social Work and is a member of Streatham Baptist Church. This review first appeared on his blog Resistance and Renewal, and is republished with permission

Baptist Times, 08/11/2016