Drawing strength from the Bible

Hazel Southam relates how the Word of God influenced Walter Young and Maude Royden

Even today Walter Young’s New Testament falls open at Romans 12. Here he would have read:

‘Hate what is evil, hold onto what is good. Love one another warmly as Christian brothers and be eater to show respect for one another.

‘Work hard and do not be lazy. Let your hope keep you joyful, be patient in your troubles and pray at all times…Ask God to bless those who persecute you – yes, ask him to bless, not to curse.’

These are words that the 25-year-old former Post Office sorter from London read repeatedly, not just through World War 1, but every week of his life. Walter didn’t want to join the war, being opposed to violence, but eventually he signed up in 1915.

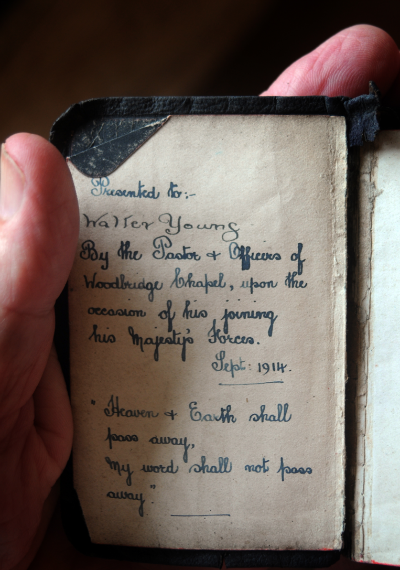

His church – Woodbridge Chapel in Clerkenwell – gave him a New Testament with the message, ‘Heaven and earth shall pass away. My word shall not pass away,’ from Matthew 24:35 inscribed in the front.

Walter was one of 65 million men to be mobilised during World War 1. One in 7 of them were killed, 1 in 3 wounded and 1 in 9 captured.

But many millions of them, like Walter, had the Bible with them. British troops were given a New Testament as a standard part of their kit when they joined up: gun, boots, uniform, Bible.

The reason, says Dr Michael Snape of Birmingham University, is that the Bible was ‘the defining influence’ on people living in Britain at that time.

‘It is hard to understand British society at the time of World War 1 if you subtract the Bible from it,’ he says.

‘It was seen as a mark of a good education, the sign of a respectable background, to know your Bible,’ he adds.

Holding services as a prisoner of war

Walter Young certainly knew his Bible, and carried it with him for all four years. But it was towards the end of the war that it really supported him – and those around him. Walter fought at the Somme, Ypres and Passchendaele. Ultimately, he was captured by the Germans and put to work as a prisoner of war in a Prussian coal mine.

‘This was about the most miserable period of my life,’ he wrote later. ‘True, life in the dirtiest and most dangerous trenches was worse while it lasted, but there was always the relief to look forward to if one survived. But life for me at this mine seemed one long round of almost unbroken misery with hardly anything to relieve it.’

Yet it was here that Walter felt that God was saying to him that his fellow prisoners of war were ‘sheep without a shepherd’. And so, he asked a German officer for permission to hold a service.

It was granted, and a series of services, using Walter’s little New Testament, were held in the ablutions room where the men washed on leaving the mine.

Walter later recalled the first service. ‘All the accommodation was occupied and some were standing and the congregation included not only British but Frenchmen and Russians as well. I suppose we numbered about 40 in all.

‘It was a strange scene for a service. There was only one light and that was partially obscured by the steam from some boiler, which made a fairly loud hissing noise all the time.

‘Nobody had a hymn book and it was obvious that only a very few well-known hymns could be chosen.

‘So from my prayer book hymnary I read out the words, verse by verse and most of them joined in the singing which was led by a violin player. It was a very simple Gospel service. I spoke a few words.

‘If anything was attempted with a feeling of unfitness and inadequacy surely it was these few services. But possibly that very feeling of weakness was my greatest strength, for I could place no dependence on myself or on others.’

A pacifist back home

Back in Britain, others drew different inspiration from the same texts.

Maude Royden was the daughter of a ship-owning Conservative MP from Liverpool, and was 38 when the war broke out.

Ahead of her time, she had attended Oxford University where she re-read the Bible and declared herself ‘considerably surprised’ by what she found: a loving God.

It was this that drew her to pacifism. She became the secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, an inter-faith peace organisation. Speaking at its launch in Cambridge she quoted Matthew 5:48 saying, ‘Christ said to us, “Be ye perfect”.’

This meant, she said, living lives of love and peace not at some later date when the world’s problems had been resolved but right now.

‘He [Jesus] did not tell his disciples that some day, when good was stronger…it would be their duty to rely on love and put aside earthly weapons of defence.

‘They were to be perfect not in the future, but “now”.’ She preached her message of peace as widely as she could.

'No other book as widely read in the trenches'

Two different lives. Two different outcomes. But the same text. Perhaps these stories show just how deeply embedded the Bible was in people’s lives 100 years ago.

Not only was it ‘consoling’ to read the Bible during the war, says Dr Snape, it also formed an invisible link between families who were separated.

‘It connected soldiers with their loved ones emotionally and devotionally as they may have been reading the same texts,’ he says.

‘It was consoling [for soldiers] to feel that you were taking up your cross,’ he adds. ‘There was an idea of purposeful suffering.’

But for most soldiers the Bible represented something familiar and reliable. It gave hope and consolation during times of extreme suffering. It was a link with home, happiness, the past and a longed-for future.

‘There is no other book that was as widely-read in the trenches,’ says Dr Snape. Walter Young was one among many who turned to it during the darkest and most difficult years of his life.

Hazel Southam is a former editor of The Baptist Times

Picture credit: Clare Kendall, Bible Society

Baptist Times, 06/08/2014