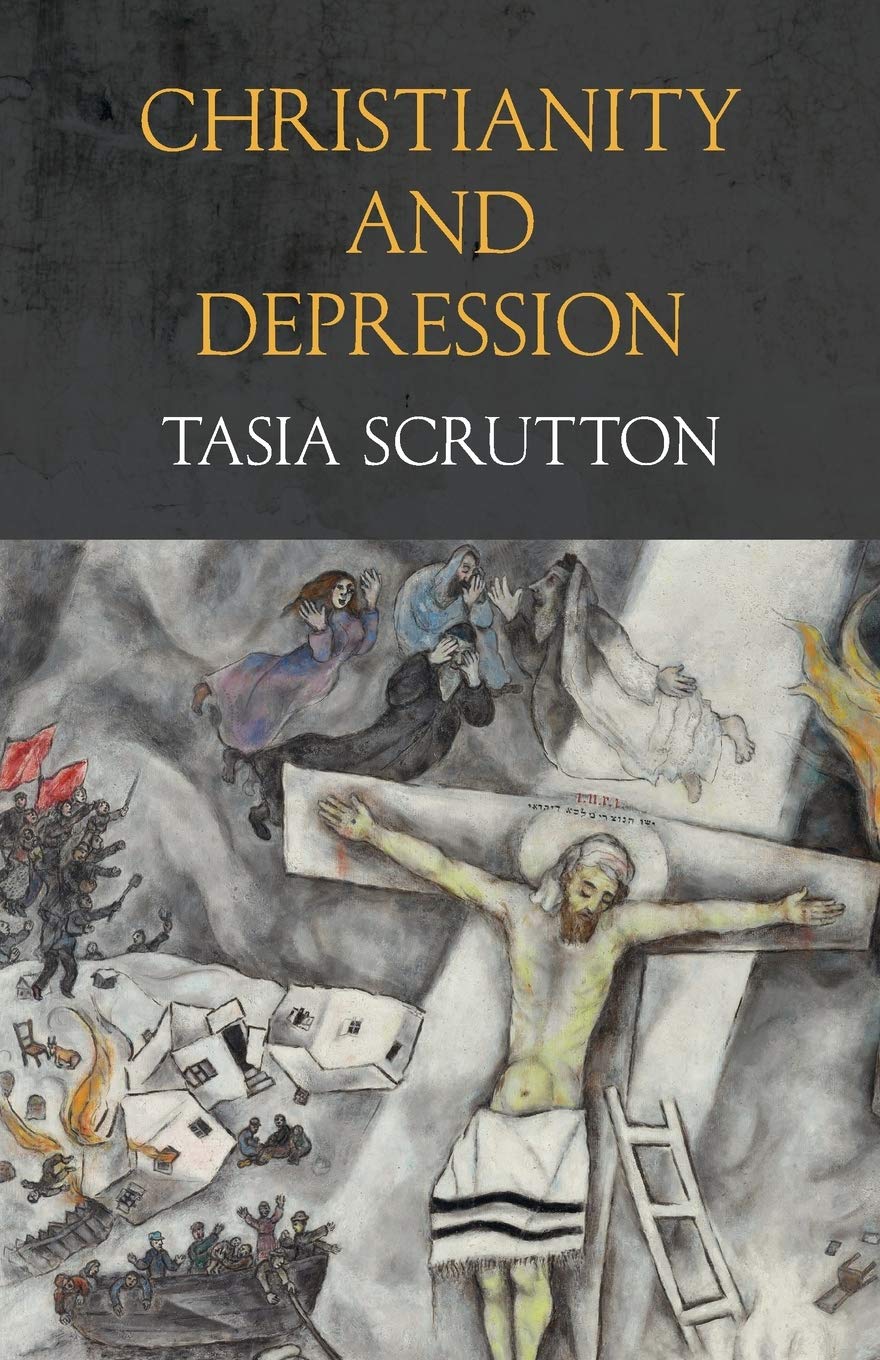

Christianity and Depression by Tasia Scrutton

An excellent, well argued book with much to commend it - more useful after an episode of depression, not during one

Christianity and Depression

Christianity and Depression

By Tasia Scrutton

SCM

ISBN: 978-0-334-05890-8

Reviewed by: Jeannie Kendall is a recently retired Baptist minister, a current tutor on the Pastoral Supervision course at Spurgeon’s College, and the author of Finding Our Voice and Held in Your Bottle ( published Sept 2021)

For many years I was director of a counselling service, where the majority of clients were suffering from depression. In addition I myself struggled with depression in young adulthood. So I came to this book, which the author says is aimed at both those who suffer from depression and those seeking to help them, with considerable interest.

Tasia has approached this huge topic by looking at some of the theological attitudes towards depression and the ways in which they might, or might not, be helpful. She begins with the notion that depression is caused by sin, which she argues in a very measured way as appearing to be helpful (in seeming to give the person control) but ultimately profoundly unhelpful as well as not theologically cogent. She argues similarly for the view that depression is demonic.

She goes on to look at biology, which she points out is useful in removing blame, but misses other linked factors such as social pressures and societal failings. She very carefully disentangles the linked areas of the dark night of the soul and depression, and treads a careful path through the ways in which thinking of depression as potentially, though not necessarily, growthful may be important.

In the sixth chapter she looks at can God suffer – the theological debate around passibilism – though in order not to display bias she presents this through a fictional radio debate, and I found this change of style out of place in comparison to the rest of the book, in which she had very adeptly set out different arguments. It read as though it had been prepared for something else and slotted in.

More usefully (I felt) the penultimate chapter looks at whether the idea of a suffering God can help, not least with seeking to reduce or remove stigma as well as offering real consolation – something which can be missing when superficial explanations or solutions are offered to someone in deep distress.

The final chapter, Towards a Christian response to depression, has some very helpful pointers based around four core emphases: Christ’s solidarity with those who suffer, revisiting the concepts of sin and demons with a more political and social slant, resurrection and hope (a very short section, disappointingly) and a consideration of our attitudes to our bodies and senses. Less than four pages are given over to therapeutic implications and I wished, given the high degree of wisdom displayed in the book, there had been more.

This is not inaccessible but it is a reasonably demanding read. I think it should most definitely figure in reading lists for pastoral care, counselling and other linked courses in any higher education setting as well as those looking to study the theological questions addressed. It would be helpful too for clinicians who may not have a faith but are seeking to understand and help those who do.

Just one caveat – I think it would be difficult for most people suffering from depression to read this book. For some it might be useful later, to try to make sense of the ways they have or have not been helped, but certainly not during an episode of depression. That aside, it is an excellent, well argued book with much to commend it.

Jeannie Kendall is a recently retired Baptist minister, a current tutor on the Pastoral Supervision course at Spurgeon’s College, and the author of Finding Our Voice and Held in Your Bottle (published Sept 2021)

Baptist Times, 03/09/2021