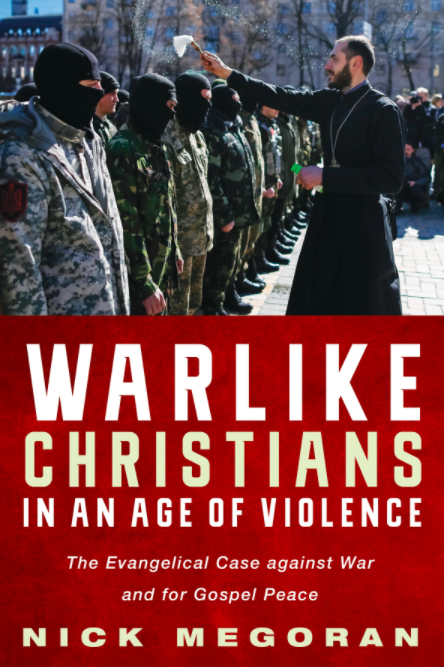

The evangelical case against war... and for gospel peace

Should the Church ever support war? Not if it's truly following the call to gospel peace, argues Nick Megoran

Nick, lecturer in the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology at Newcastle University and member of Heaton Baptist Church, is the author of new book Warlike Christians in an Age of Violence. He explains more in this interview

Why did you write the book?

As a student of politics and international relations in the 21st century, I study the carnage that war and violence wreak on creation and humanity. As a Christian I see in the Bible a fine diagnosis of the problem (war as a manifestation and consequence of sin, as Martyn Lloyd-Jones put it), and a marvellous solution to it in what the Apostle Paul calls “the gospel of peace.”

Yet for too much of our history, the church has supported whichever ‘just war,’ crusade, rebellion, or ‘humanitarian intervention’ its host nation has been involved in. We have been warmongers rather than peacemakers, to the shame of the cause of Christ. I wrote this book from the conviction that in the gospel we have so much more to offer the world.

How is it different to the numerous other Christian books on war?

Theologically, it is thoroughly evangelical. First, it insists on the supremacy of scripture as “the only rule of faith and obedience,” in the words of the Westminster Confession.

Second, it is grounded in the Reformation doctrines of grace, placing justification by faith at the heart of its reasoning.

Third, it assumes that the Holy Spirit is dynamically and miraculously at work in the world’s war zones, enabling Christians to make a distinctive contribution to peacemaking.

It is also different in its use of evidence. Most Christian books on war are written with reference largely to other Christian books on war, rather than being grounded in detailed studies of what war actually is. In contrast, this one uses my own fieldwork across three continents, and mines Christian histories and biographies set in conflict zones around the world, for remarkable and inspiring examples of what Christian peacemaking can look like as an alternative response to war.

Where does it stand on the old debate between pacifism and just war?

Both of these approaches are bound to lead our thinking astray because they start with a set of human theories which they impose on the Bible. Just war theory was a pagan Roman idea adopted by the medieval church, and pacifism is a modern liberal idea. Neither maps remotely onto either Old or New Testaments, and if you start from one of these human philosophies with all their problematic assumptions you will inevitably end up in the wrong place.

What I call “Gospel Peace” in contrast is the contention, drawn from scripture, that the church’s primary response to war is to simply be the church, by preaching the gospel and making peace in the love and power of God. And, of course, this means that there is no possible way in which Christians could legitimately serve in militaries, guerrilla armies, terrorist groups, United Nations forces, and the like. It is inconceivable that Christ could have killed his enemies, and it is inconceivable from a Biblical perspective that we could kill our own.

Doesn’t the Old Testament support the argument that Christians can take part in just wars?

No. In the Old Testament the laws of war were most clearly not there to help any country judge what a ‘just’ war might be. Rather, they existed only for Israel in its condition as a territorial state at a certain time in history, to produce faith by their conduct (intentionally military weakness thus reliance on God) and holiness by their outcome (keeping Israel apart from idolatrous temptations). They were part of the law, which was “only a shadow of the good things that would be found in Christ” (Hebrews 10:1).

With the death and resurrection of Christ, the laws on war went the way of temple worship, animal sacrifices, and Levitical dietary and clothing regulations. To use the Old Testament to justify Christian violence today not only runs roughshod over any sound evangelical exegetical tradition, but is to prefer the law to the gospel. It is, in effect, to deny the life, death, resurrection, and ongoing ministry of Christ.

But hasn’t church history showed that the church has allowed soldiering?

The early church, for centuries, resolutely held to New Testament gospel peace. An important document on church order in the early third century, for example, listed soldiering alongside brothel keepers, gladiators, idol makers, astrologers, and prostitutes as professions forbidden to those seeking church membership: the man “who wants to become a soldier is to be rejected, for he has despised God,” it concludes.

This changed when the church later sold out on holiness to gain political influence by cosying up to the state, in what historians call ‘Christendom’. The effect of that was disastrous, for the world and the church. As a result, today many people reject Christianity because they can point to the role it has had in crusades, wars, torture, and the like, down the ages. That is our greatest shame and for many today the greatest obstacle to the gospel – an obstacle we reinforce every time we justify Christian soldiering.

But at each stage of church history, particularly at periods of great revival and reformation when the scriptures have been rediscovered, Christian movements and thinkers have arisen who have returned to the New Testament model of gospel peace. Today, these people and movements are not so much found in the West, but amongst the church facing the violence of Islamic State, Boko Haram, and other such groups in Africa and Asia.

On a related note, one strand of Christian thinking is that while they support peacemaking in general, in extreme cases war is needed (ie to stop tyrants like Hitler). How do you argue against this?

This difficult question is discussed at length in the book. It is difficult not because the answer is hard, but because in American and British popular film culture World War 2 has taken on an extraordinary identity story as a “feel-good war” of goodies versus baddies. In reality, it was a clash of imperial powers for global dominance, where morals played second-fiddle. For example, the USA and UK closely supported the USSR – even though Stalin had murdered some 25-30,000 priests and more millions of his own people than had Hitler.

But we went to war with Hitler rather than Stalin because Hitler threatened global dominance more than did Stalin. The churches in all belligerent countries – Japan, Italy, Germany, Finland on the Axis side as much as Britain, the USA, Russia, and France on the Allies – proclaimed that God was on their side. If they had all condemned the war on one day and refused to let their members fight, the Second World War could never have taken place. That this didn’t occur was a failure of discipleship of the first order. World War 2 was one of the greatest disasters in Christian history, and led many in the non-Western world to reject our faith in horror. Christian ethics should be based on Holy Scripture, not on Hollywood.

Do you think Baptists should have a particular view on war?

No, our view should be moulded and informed by primarily by scripture, as should those of all Christians. But I would hope that our noncomformist history, our origins in continental Anabaptism, and our insistence on freedom of conscience to interpret scripture rather than obedience to church dogma, sensitise us more to how complicity with state power can deform the church. Likewise, at best our congregational models of church governance, with practices of discipleship, membership, and discipline, can also help in this regard – if they are working well. So it is perhaps no surprise that two thinkers I return to again and again in the book are Baptist ministers Martin Luther King and Charles Haddon Spurgeon, who were both implacable critics of war and advocates of what I call gospel peace.

Thus I do think Baptist churches have an easier job of disentangling themselves from violent histories than do many other denominations, especially those who enshrine ‘just war’ in their teaching. That said, we must not think we are in any way immune to the terrible errors of Christian militarism: as Baptist historian Paul Dekar puts it “In the past, the complicity of Christians in war-making and vacuous bleating by Christians about love or peace have discredited Christianity.” That’s a history we all have to take responsibility for.

You argue that we could be entering one of the most exciting periods of church history. Could you say a little more about this?

The worldwide church is changing, driven not only by reflection in the West on the disastrous experiment with ‘just wars’ under Christendom, but also by our brothers and sisters in Africa, Asia and Latin America who face violence every day but who call us to respond Christianly. I see this rejection of violence as simply the latest stage of the Reformation, begun by Martin Luther exactly 500 years ago and continuing today. The unbiblical idea that Christians can fight and kill other people is going the same way that the unbiblical idea they could buy their way out of purgatory went.

This frees us up to truly be church and to preach and live out the gospel in a manner that has been impossible for most of us for centuries. The book is crammed full of amazing and inspiring examples from around the world and throughout history of how Christians can challenge war and be peacemakers. Some of these are people and stories I got to know through my involvement with the Baptist World Alliance’s Commission on Peace and Reconciliation. One of the things I am most proud of about the book is that it is endorsed on the back cover by Jeffrey Brown and John Enyinnaya, African American and Nigerian Baptist leaders respectively, who have done so much to point their countries to the ways of gospel peace. They are part of the ‘cloud of witnesses’ who point us to the enduring relevance of authentic Christian peacemaking.

So I am not much concerned by reports about the decline in influence and numbers of the church in the West. Rather, I think we may be on the verge of one of the most vibrant and exciting periods in the history of the church.

Nick Megoran is Lecturer in Political Geography at Newcastle University, and a member of Heaton Baptist Church, Newcastle. He is a Baptist Union of Great Britain representative to the Baptist World Alliance, and co-chair of the Martin Luther King Peace Committee. He is the author of Warlike Christians in an Age of Violence, published by Wipf and Stock

Baptist Times, 08/11/2017