The Penultimate Curiosity

Well written and beautifully produced, exposing the falsity of the ‘conflict myth’ about the relationship between science and religion

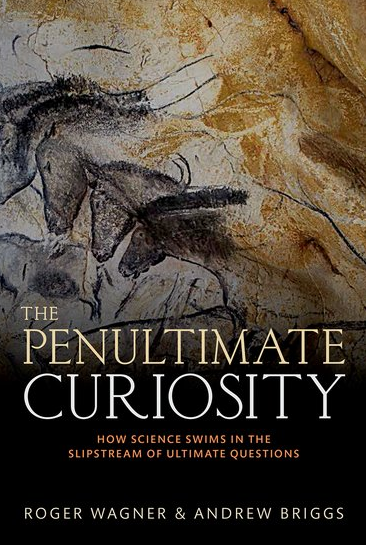

The Penultimate Curiosity: How Science Swims in the Slipstream of Ultimate Questions

The Penultimate Curiosity: How Science Swims in the Slipstream of Ultimate Questions

Roger Wagner & Andrew Briggs

Oxford University Press

ISBN 978-0-19-874795-6

Reviewed by the Revd Dr Ernest C. Lucas

This fascinating book has an unusual pairing of authors, an artist and the Professor of Nanomaterials at the University of Oxford. It had a starting point in the authors’ observation that both the University Museum in Oxford and the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, each among the earliest purpose-built scientific institutions in their respective universities, have religious invocations set over their entrances.

Investigation showed that these were not mere pious gestures but represented the deeply thought-out convictions of two central figures in the Victorian scientific world. What led to their impulse to integrate the domains of religion and science?

The book’s main thesis is indicated by its sub-title. The human drive to seek answers to ultimate questions, to make sense of the world as a whole, has provided a ‘slipstream’ which has encouraged, shaped, and often helped, the search for answers to penultimate questions, the desire to understand the physical world.

What the authors call ‘ultimate curiosity’ takes a religious form when it leads to the conviction that ultimate answers must come from something or someone that transcends the world.

‘Penultimate curiosity’ has led to modern science. The ‘slipstream’ metaphor comes from the V-formation adopted by flocks of birds because this reduces the energy expended by the birds flying in the slipstream of those in front. The same principle leads to the formation of pelotons by the riders in cycle races.

This book covers ground that is covered in others on the history of science, so what is different about it? One thing is the way it presents much of the history by telling the stories of key people whose life and thought provide examples of how the two curiosities interweave in various ways and how penultimate curiosity has been motivated by the ultimate curiosity. Many of the stories are fascinating and this provides an interesting way into the various issues concerning possible ways to integrate science with religion, some more helpful and productive than others.

The book has a much wider scope than most, from what is known about the beginning of human culture to the questions posed for religious belief by science in the 21st century.

The discussion of the evidence for the rise of ‘ultimate curiosity’ in prehistoric humans, as seen in various artefacts including cave paintings, in Part 1 is particularly fascinating and will probably break new ground for many readers. More space than usual is given to the contributions of Islamic and Jewish thinkers. Part IX deals with biblical archaeology. There is a very helpful and thought-provoking Epilogue which pulls the threads of the book together.

The book is well-written, lavishly illustrated with relevant pictures and diagrams, and beautifully produced. It is a pleasure to read.

More importantly, it deserves to be widely read because in a culture which, encouraged by the media, still believes the ‘conflict myth’ about the relationship between science and religion, it exposes the myth’s falsity and the possibility and potential fruitfulness of a continuing interaction between the two ‘curiosities’.

The Revd Dr Ernest C. Lucas was Vice-Principal and Tutor in Biblical Studies at Bristol Baptist College until he retired in 2012. He is an Honorary Research Fellow in Theology and Religious Studies in the University of Bristol. The course he taught on Science and Christianity received a Templeton award, as has a paper he has published on Science, Wisdom, Eschatology and the Cosmic Christ

Baptist Times, 01/07/2016