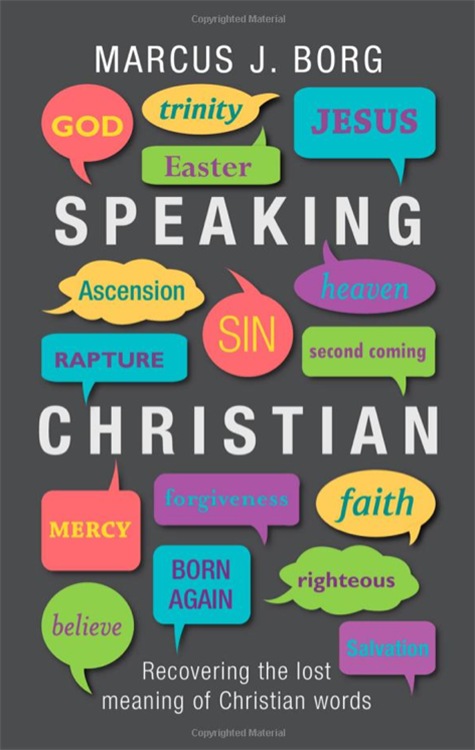

Speaking Christian: Recovering the Lost Meaning of Christian Words

The American author, Marcus Borg, is concerned about unfamiliarity with biblical witness in the current generation and fears that what is known is neither believable nor accessible to the modern mind

By Marcus J Borg

SPCK, £10.99

ISBN: 978-0-281-06506-0

Reviewed by: Stephen Copson

In short, Christians speak a different language. Moreover, he argues that whilst usually vocabulary and concepts evolve, much Christian language and the framework that gives it meaning has been trapped in cultural expressions that are now unsupportable.

This is the “heaven-and-hell-framework”, where the purpose of religion is to negotiate the individual safely through the perils and pitfalls of this life to enjoy the rewards of the next. Jesus is the key to Heaven or Hell and deals with the sin that separates people from God, which he achieves through his redemptive death and resurrection. Believing and being a Christian means accepting that these things are true.

Borg locates the emergence of this theological mindset in the Constantinian settlement. Now he argues is the time to return to the biblical witness and free the language of the baggage of the centuries. He rejects the “pie-in-the-sky-when-you-die” argument and asserts that the good news is about how to act in the world. The purpose of faith is to transform the present world and Jesus is the one who points the way and embodies the message, even to death on a cross.

Accepting this worldview radically challenges Christian vocabulary. God is sacred presence, immanent rather than “out there”, albeit expressed through personality. Theological language given this new context acquires fresh significance. So righteousness translates as justice; mercy is compassion, salvation is social transformation and belief is having the right attitude to others, or “beloving”. Easter, Ascension, Pentecost and Trinity become signposts in this new reality that point to the truth. He wishes to retain traditional language but totally change the meaning.

Surely the author is right to propose that language and concepts (his own included) are sensitive to cultural shaping; surely he is right to offer a corrective to a dominant literalism that denies a rounded appreciation of biblical parable, poetry, metaphor and myth and surely he is right to challenge a deadening fundamentalism that vitiates the rich witness of the scriptures, stifling religious imagination with the dead hand of dogmatic assertion.

But perhaps in his effort to make the argument, he is tempted into shorthand. He assumes atonement theory equals penal substitution. Conservatives are uncaring about issues of justice and the environment, Creeds are archaic and the Trinity mystifying. Brief chapters do not help detailed explanation. And must it be either/or?

Marcus Borg is an American Episcopalian writing in the context of the social, political and religious influence of conservatives and fundamentalists (he tends to conflate the two) in America – although their influence has travelled far. His concern is for people unable to accept this interpretation who choose to walk away from Christianity completely. It is theology written out of pastoral care.

This is a thought-provoking book and the Church needs creative theologians who are passionate in exploring truth, but it leaves me with a sense of unease that by rebutting literalism, the obvious question is missed: if Christians have simply failed to understand or misapplied the central matters of faith for nearly all the history of the church, not to mention most of the two billion Christians on the planet today, then how much credibility does Christianity have?

Stephen Copson is a regional minister for the Central Baptist Association