25th July 2017

I haven’t been doing much work on the lecture recently. Partly, this is because I was away in Beirut at the Arab Baptist Theological Seminary’s annual Middle East Consultation. If you’re interested, you can

read some of my reflections on this extraordinary conference here

However I would like to offer some thoughts on a chapter of Kings I re-read recently. In 2 Kings 9 and 10, we read of the violent actions by one Jehu, who has just been anointed king of Israel by Elisha. Inconveniently, Israel already has a king (Joram, son of Ahab). But Jehu doesn’t let a small matter like that get in his way. Even though Joram is wounded from a recent battle, Jehu strikes him down. And as the king of Judah happens to be there at the time, Jehu kills him as well. Two-for-one day on regicides. Oh, and he kills the queen mother for good measure.

So far, so standard. The kings of Israel don’t tend to have long dynasties. Knives were sharp and ambition was strong at that time. And Ahab’s family is subject to condemnation for Ahab’s actions over Naboth and his vineyard. But read on to chapter 10, and the violence piles up – quite literally.

Joram had seventy sons, seventy grandsons to Ahab. (Presumably he had a few concubines!) They may still have been quite young - the Hebrew is ambiguous, but the ESV’s reference to ‘guardians’ may be correct. But, young or not, they pose a threat, and as long as they are alive, Ahab’s family lives on. So Jehu proceeds to murder them – or rather, to manipulate their guardians into murdering them, as proof of their transferred loyalty. In demonstration of their deaths, their heads are piled up in two heaps at the gate of Jezreel. Nice visual.

And Jehu is far from done. He also wipes out the entire family of the king of Judah. Forty-two people. ‘Take them alive’, Jehu says – and then throws them all into a pit and slaughters them.

Finally, Jehu tricks the prophets of Baal into revealing their religious affiliation, by pretending to hold a religious festival in the god’s honour. Then, at the height of the festivities, he slaughters them all, demolishes their temple, and befouls it with human excrement. The body count in these two chapters is pretty staggering.

What are we to make of such a story? In particular, how are we to read this ethically? Because, on the surface of the text, God appears to approve whole-heartedly of Jehu’s actions. 2 Kings 10:30 says, ‘The LORD said to Jehu, “Because you have done well in carrying out what is right in my eyes…”.’

The problem is that we are often lazy with our use of the Bible. Convenient text-mining for verses of comfort (“I know the plans I have for you, says the LORD…”) can teach us to do the same thing in much more dangerous ways. Perhaps these verses could be taken as justification for a religious purge in our own land… you can see how the unimaginable could be argued, I am sure. Poor use of scripture has certainly incited violence in the past.

So I’d like to suggest two principles to help us read this passage ethically.

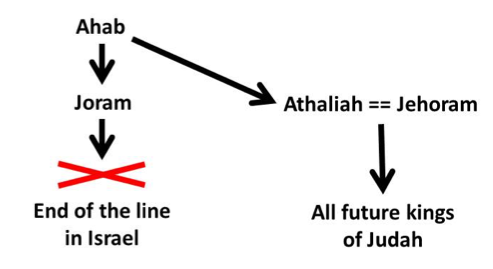

1. Don’t assume that the surface meaning is the take-home message. Because while Jehu is busy annihilating the house of Ahab in the northern kingdom, something very interesting is taking place in the southern. You see, Athaliah, Ahab’s daughter or sister, is the queen mother in Judah. This means that, henceforth, all the kings of Judah will be descended from Ahab. (See the family tree if that’s confusing.) Jehu has not eradicated the house of Ahab – it has sprung up in the royal house of David. Jehu’s ‘zeal’ for the eradication of Ahab’s family is ironically undermined by the text itself.

2. Notice where there are multiple voices in the biblical witness. Does God approve of Jehu’s actions? Yes, says the author of Kings, although with the caveat that we noted in point 1. But turn to Hosea, and we read that God instructs him to name his first son after Jezreel, the town where those heads were piled up: ‘because in just a little while I will punish the house of Jehu for the blood of Jezreel’ (Hosea 1:4).

It’s not easy to work out how to formulate a unified opinion when there are two such different evaluations of the situation. And this is perhaps the point.

Unlike many ancient Near-Eastern texts, which consist entirely of official propaganda from the state, our Old Testament contains a rich variety of texts, from a great variety of authors, poor as well as wealthy, marginalised as well as powerful. And as a result it sometimes contains multiple points of view on the same matter. Should this undermine our appreciation of it as the word of God?

I think not, although it might cause us to be more wary of carelessly lifting texts to support our particular cause. The term for these multiple voices is polyphony – like a choir, with different people singing different parts. Usually these parts harmonise, but sometimes they clash. And we will understand our Bibles better when we notice those clashes, and don’t try to smooth them away. The truth will best be found at the point where the texts collide.

‘Israel’ means ‘he wrestles with God’, and the Old Testament is a record of that struggle. God’s truth is bigger than a single text can tell us. We will get closer to it if we notice the wrestling of the text, and if we join in.

This blog is part of series, please click here to read more.

For more about the Whitley lecture.

The 2017 Whitley Lecture is entitled the

The Pioneering Evangelicalism of Dan Taylor (1738-1816) by Richard Pollard, Minister and Team Leader, Fishponds Baptist Church, Bristol. It is available from

Regent's Park College.

The 2016 Whitley Lecture was

Church Without Walls: Post-Soviet Baptists in the Ukranian Revolution 2013-14 by Joshua Searle, Tutor in Theology and Public Thought and Assistant Director of Postgraduate Research at Spurgeon's College

.