‘Anecdotal history’ matters; those stories which amuse, amaze and inspire us, from which we draw identity and strength because they tell of people ‘like us’. I treasure the story of the woman who served faithfully in one of our London churches for many years. One day, she was faced with a man (whom she described as standing too close) who said to her “I don’t believe in women ministers”. She responded calmly “Well, now you are confronted with reality”. Her story was one I drew on only the other week, when I faced the same situation, some 40 years later. (Though I cannot claim to have her self-possession, or aplomb).

Another of our foremothers delighted in telling the story of how, since only male students were allowed to live in college, she would, after working in the evening in the library, sneak out through the toilet window, aided and abetted by her male colleagues. A story I held on to when I went to college, and discovered that, despite the college having accepted women for many years, there was still no ladies’ loo.

There’s the grace with which another dealt with the question at a ministerial recognition interview; “What will happen if you become pregnant?”

She gently replied “I’ll have a baby…”

I was privileged to work with another woman who served for nearly 50 years in one church. I was with her at a meeting in the church we both served. A minister attending assumed she was there to provide tea, and put in his request accordingly. She made the tea, handed it over (with a beaming smile) and then took her place as chair. She said to me later: “You’ve got to laugh – it’s more productive than crying”.

Stories to treasure, to tell, to hang on to… but not enough.

Because though these stories inspire, encourage, make those of us who follow in their footsteps thankful for them, it still keeps women in ministry as an anecdote, an oddity, a side issue to ‘real history’.

Therefore, it is important that we tell the ‘formal’ history of women’s ministry among Baptists. As Karen Smith pointed out nearly 30 years ago, too much of our historiography has the shape of ‘history of men by men for men’.

1

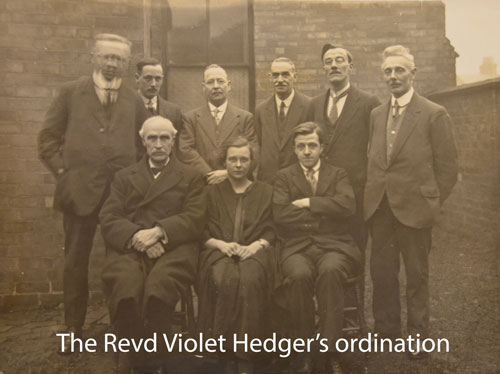

This centenary is a good opportunity. But Violet Hedger was not the first woman whom Baptists recognised.

One of our older churches, Broadmead in Bristol, was begun in the 1640s when the wife of the minister of one of the parish churches, Dorothy Hazzard, drew around her several like-minded friends who were convinced that the establishment of the church (its political control), and the use of a prayer book (set words, rather than those inspired by the Spirit) were contrary to scripture. They started to meet separately, they eventually called a minister and organised themselves as a Baptist congregation. And to this day, Dorothy Hazzard is honoured among that congregation as a pioneer church planter.

There was also Mrs Attaway, who was cited by Thomas Edwards in his denunciation of the sectaries in his book Gangraena (published in 1646). Attaway held a Tuesday afternoon lecture, at which she taught scripture and exhorted the company – and to which she drew up to a thousand people.

2

And time will fail us to tell of women who witnessed, who taught, who wrote hymns – who played their part not just as members of the congregation, but also as those who communicated the faith in a variety of ways, with pen, voice and life. They may not have been recognised as ministers, but they exercised ministry.

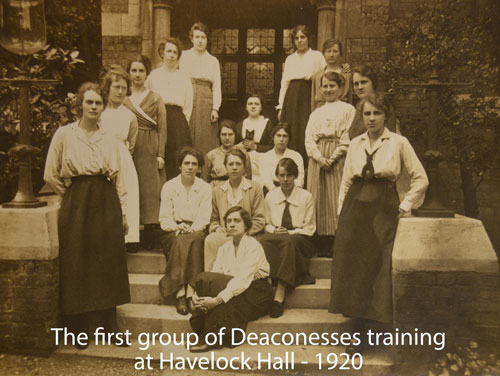

A recognised form of ministry emerged, even before Violet Hedger went to college. 1890 saw the beginning of the Deaconess Order, women who served as missioners, social workers, church planters, community developers. Their story is told elsewhere in this publication, and it is an important one that is not well-enough known. The history of women in ministry without their history is partial, not the least because of the confusion that emerged about different forms of ministry. The presence of the Order meant that, for too long, the denomination could ignore wider issues.

One of the reasons why the Order ended was because, by the mid-70s, women were now recognised as ministers, and so it looked like a more proper (and indeed, Baptist) path for women with a call to pursue. That some were called to diaconal service and lost that sphere is one of the ironies that emerges – and which requires reflection.

But even with the story of the deaconesses noted, Violet Hedger is not the first woman minister. The first formally recognised woman that we know was Edith Gates, called as pastor of Little Tew and Cleveley, Oxfordshire in 1918. She served, over a growing work there, until 1950. She did not go to college, but sat the exams for non-collegiate candidates, and was duly enrolled onto the probationers’ list in 1922.

Another woman enrolled at the same time, Maria Living Taylor, served as joint pastor with her husband in various churches.

As we explore their history, it is important to place it in the context. As well as celebrating a hundred years since Violet Hedger went to college, we celebrate a hundred years of (some) women having the vote in the UK. WWI had a significant impact on the perceived place of women in society – and their capacity to take on new roles.

But it is worth noting too, as Timothy Larsen has recently written in Reformed Journal, there is a long history of women taking public roles in evangelicalism; among Methodists, the Salvation Army and, in the early 20th century, the early Pentecostal denominations. And we should not forget that the beginnings of suffragism are in evangelicalism; the Pankhursts, for example, were very clear that their call for women to have the vote had a theological basis.

But as we explore the history of Baptists, there are questions we need to ask. Who were these women, how did they discern a call, what did they face as they explored it and what did people think of them? There is work to be done here, including exploring the place of local churches in discerning and affirming calls; both these women were recognised by the Union because they had already been recognised by their local congregation. The Union then recognised them, first as probationers and then, not as ministers but, ‘women pastors’. This was a separate list in the handbook until 1956, when it was changed to ‘women ministers’. From 1966, there has been one ministerial list. In 1967, our Union received a report Women in the Service of the Denomination which stated: ‘The Committee believes that witness-bearing and ministry are the continuing responsibility of the whole Church; … and that there are no grounds of principle or doctrine for debarring women duly qualified from any of the special forms of ministry.’

Which is to say, women and men are recognised in the Union for ministry on the same basis.

Of course, saying it and living it are not the same and this report did not mean that immediately women’s ministry was accepted. The numbers didn’t dramatically increase. After Edith Gates, Maria Living Taylor and Violet Hedger, the next woman to be recognised was Gwyneth Hubble, in 1938. She did not serve in a church, but trained deaconesses. A gap, then the 1960s saw a little flurry – the women mentioned at the beginning of this article were all ordained in the early 60s, and knew themselves as a group, meeting regularly (when they could). These women, joined by some who had become deaconesses in those years, and then were ordained at the end of the Order, consciously built a firm foundation, and encouraged younger women to consider and to pursue a call – and I was one of them. Much of their story was told in a 2014 Baptist Quarterly article by Faith Bowers.

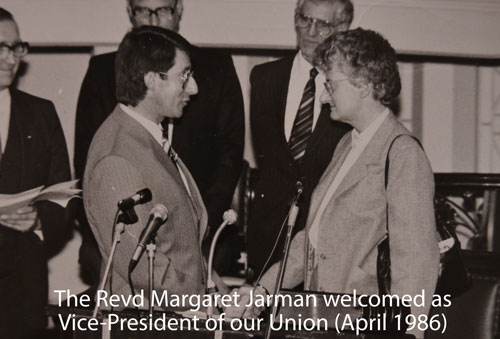

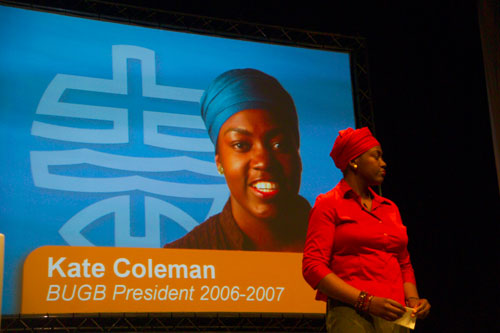

There was a steady though small flow of women into ministry in the 1970s and an increasing number in the 1980s, including one who went on to be Deputy General Secretary of the Union, Myra Blyth; several who served as college tutors; one who became the first woman minister to be President of the Union in 1986, Margaret Jarman, a deaconess who became a minister (and the first woman student at Spurgeons); one who served for the BU with the World Council of Churches, Ruth Bottoms; and many who served local churches. The 1990s saw the appointment of Pat Took as the first woman Superintendent, and the next decade saw several women called to significantly large or historic churches as sole or lead pastor, as well as the first black female accredited minister in Kate Coleman. Kate would go on to serve as President in 2006-7, and in 2013 the Union appointed a woman, Lynn Green, as General Secretary.

In the mid-80s, an annual meeting of women ministers began, which would last a couple of decades. Such a gathering offered several things; the discovery that we were not odd, there were several of us (a recognition not to be underestimated), the discovery of our history through meeting those who had gone before, and the possibility of affecting policy and expectation. Maternity leave was written into terms of settlement (though we failed to get paternity leave included at that point – not for want of trying), and we got issues around settlement and the shape of training considered by those who had responsibility. Various statements and undertakings were made, such that the then superintendents, and now regional ministers, agreed to challenge churches who refused to consider women during vacancies, colleges worked to ensure that women students were not barred from preaching in certain churches, and modes of training were examined. All of these – often behind the scenes – actions have changed the landscape considerably.

The proportion of women candidating for Baptist ministry is still lower than other denominations, and it is not easy to disentangle the reasons for this. There are still churches where women cannot be deacons, let alone preach or be pastor. There remain those who maintain – and have no difficulty in telling us so – that women should keep silent.

But then, we never did agree on everything, so why should this be different. There remains a distance to go, but even in my ministry life (30 years this month) I can see important changes.

And as we sometimes mutter and feel frustrated, it is salutary to remember Violet Hedger, and Edith Gates and Maria Living Taylor… on their grace, their courage, their conviction, we build. And we give thanks for them.

1

Beyond Public and Private Spheres: Another Look at Women in Baptist History and Historiography in

Baptist Quarterly, Vol. XXXIV, April, 1991, pp 79-87

2 For more on Mrs Attaway and other women doing interesting things, see Curtis W Freeman (2010)

Visionary Women among early Baptists in

Baptist Quarterly, 43:5, pp 260-283

Ruth Gouldbourne

Ruth Gouldbourne is minister at Grove Lane Baptist Church in Cheadle Hulme, where she started in July 2018.

Before that she had been part of the ministry team at Bloomsbury Central Baptist Church in London, where she moved after teaching history and doctrine in Bristol Baptist College for eleven years. Her doctoral research covered issues of gender and theology in the radical reformation and since then she has written on Baptist identity and history in various contexts, and on women and ministry in various other contexts. In 1998, she was the Whitley Lecturer, exploring aspects of women and ministry in Baptist history. She was ordained 30 years ago, has been privileged to be mentored by various amazing women, and is delighted that her calling is not so unusual nowadays.

Photos from the

Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford

This article was first published in the Spring 2019 edition of Baptists Together magazine