When is a minister not a minister? For many years women exercised ministry in our Union as deaconesses. Julie Aylward traces their story

The first deaconesses were recruited in 1890 when Dr F B Meyer and the Revd Hugh Price Hughes became concerned about the moral and social conditions of the population. The Sisters had a ministry of comfort to the poverty-stricken people: ‘to help and to brighten the lives of men, women, and children and most of all to win them to Jesus Christ.’

1

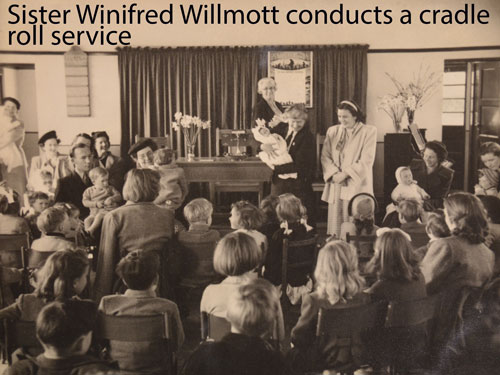

Many were qualified nurses but they also conducted mothers’ meetings, taught in Sunday School, visited people in their homes: scrubbing their floors, cleaning their homes, nursing their children, tending their sick, and sitting with the dying.

By 1907, 20 deaconesses were working in London. Sister Lizzie Hodgson was attracting 500 women a week to her open-air meeting and preaching on Sunday nights filling the Lyric Theatre, (capacity 1400). Gradually they were posted to the ‘provinces’ and South Wales, or as missionaries.

Deaconesses were not allowed to marry as it was believed they would be unable to fulfil the duties of wife and mother and be a deaconess, though this later changed.

During the 1914-18 war deaconesses began to take on churches where ministers enlisted. When the men returned the women graciously stood aside. This was repeated during the Second World War.

This development led to Baptist leaders questioning the rights of the church to deny women the opportunity to enlarge their ministry. In 1915 Dr Charles Brown said: ‘the Sisters are as truly ministers of Christ as the men ordained to the ministry of the Word’.

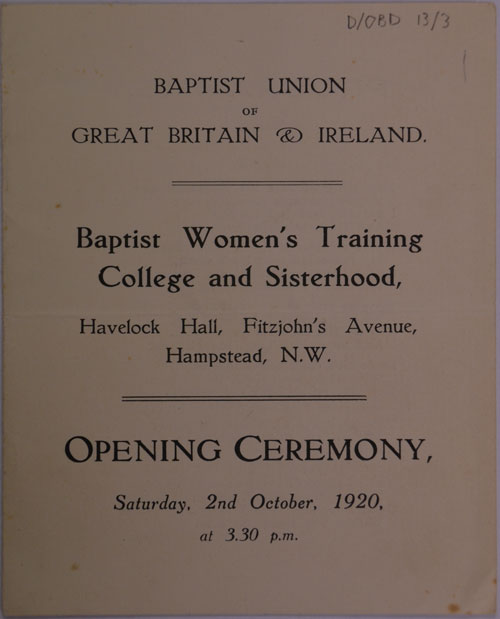

2

The Sisterhood became an official part of the Baptist Union in 1919, recognising the important work they were doing in churches. Deaconesses were a solution to the problem of urban churches: building up failing churches or planting new ones where the men refused to go because the pay was poor, with harsh conditions. They developed churches till they could afford a male minister. One source of pain was that the establishment of the church was often dated from the arrival of the male minister.

One Sister commented: “The women went where only the women could go and reclaim the people and that was because only women were likely to give themselves to sordid menial beginnings of the task which had to be done’.

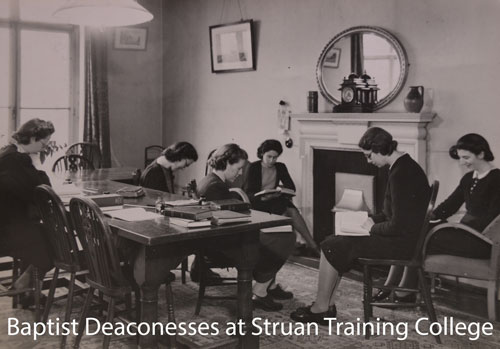

3

As the work progressed so did the training: speaking at meetings, theology, Bible study, elocution, and the cultivation of the spiritual life. Later New Testament Greek, apologetics, homiletics, church history, and psychology were added.

By 1932 there were eleven Sisters in pastoral charge of a Baptist church, three ordained as ministers. Whilst women were allowed into ordained ministry the majority preferred to train as deaconesses, believing that they should be in a servant role rather than in the leadership role traditionally associated with men.

The advantage for churches was the much smaller financial commitment: deaconesses had a very minimal stipend and no requirement to provide a manse.

Duties varied immensely: initially permission was often not granted for preaching in church, presiding at communion, or performing baptisms. Eventually they were allowed to preach and preside but a restriction remained on baptisms, either for reasons of modesty, or for fear that they were not strong enough - this too changed.

By 1945 an increasing demand for deaconesses resulted in several recruitment drives. However, a rise in stipend prevented poorer churches from having even a deaconess and so demand reduced.

In the 1960s four of the Sisters, who were effectively doing the work of a minister, decided to seek ministerial recognition, which they were granted - but without financial support from the Baptist Union.

Despite the fact that the Union saw no objection to women as ministers, enquirers were directed to the Deaconess Order. This suited most but for some this response represented a crushing blow to what they believed God was calling them into.

Resistance came not from the structures of the Baptist Union but the churches. They were happy to accept a deaconess fulfilling the ministerial role, but were very resistant to a female minister. One deaconess reports that even though she had been in sole and full pastoral charge of the church, when she gained accreditation several families left, objecting to her being a minister in the same role.

Thus began the journey towards the decision for all active deaconesses to be transferred to the accredited ministers’ list. This was no easy decision for the women, many of them feeling that there remained a distinctive role that deaconesses could fulfil.

‘When our Order finished, a number of our Sisters were very sorry to lose the title sister and to be called Rev... because the deaconess is one who serves... every person is different and everyone has different gifts we fulfil a different role. I do feel that the roles of men and women are complementary, each have their part to play.’

4

However, after much heart searching, the Deaconess Conference in November 1974 took the difficult decision to agree to the transfer.

On 23 January 1975 the Deaconess Council met and issued the following statement:

‘Believing that the function of the Deaconesses has, under God, become that of a Minister, agree… to the transfers of the Deaconesses to the ministerial list, and the dissolution of the Deaconess Order.’5

Some deaconesses chose that moment to retire, others moved onto the accredited list, but took some time to adjust to the new status that they had.

The Baptist Union had been on a long journey and it seems that the existence of the Deaconess Order had been used as a way of avoiding the difficult task of commending women in ministry to the denomination and that the women had been allowed to do the work of ministry without the recognition.

On 26 June 1975, 80 deaconesses were transferred to accredited list. There was a thanksgiving service at the next Baptist Assembly. It was recommended that all deaconesses had some kind of service to mark the change of status.

At the 1977 Assembly Ernest Payne reflected that the Union had too often ‘left to the women jobs that had daunted us men’ and that although the Baptist Union should be proud of the Deaconess Order:

their pride must be touched with a bit of shame because so many of the stories have behind them a great deal of heroism and heartache… quite frankly we have not as a denomination given them adequate support or recognition.6

When is a minister not a minister?… when they are a Deaconess.

7

1 Rose, Doris, M,

Baptist Deaconesses (London: The Carey Kingsgate Press Ltd, 1954) p6.

2 Rose, Doris, M,

Baptist Deaconesses (London: The Carey Kingsgate Press Ltd, 1954) p12.

3 Sister Lena Parkinson. ’Sisters of the People: the Passing Years’

4 Sister Winifred Waller interview

5 Deaconess Committee minutes, 23 January 1975.

6 Cassette tape April 1977 ‘Sisters of the People’.

7 Margaret Jarman in undated leaflet found in Deaconess archive in Angus Library Oxford

Julie Aylward

Julie Aylward is a Baptist minister currently serving as a prison chaplain.

Research on the Deaconess Order was done as part of sabbatical studies and is ongoing. She writes: I am indebted to The Angus Library for access to their archive and especially to Nicola Moore’s paper: Sister of the People The Order of Baptist Deaconesses 1890-1975. This is inevitably just a glimpse of the amazing story of the work of Deaconesses in our denomination serving the gospel in the most inhospitable places for little pay or recognition.

Photos from the

Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford