The Church, the far right, and the claim to Christianity

The far right has grown in prominence in recent years - with some cynically employing Christian-sounding language even though their allegiance and values are quite contrary to Christian ones.

Helen Paynter highlights the current context - and how the Church can respond

"The Radical Right is blossoming. 2023 is the year it came of age." Hope Not Hate, State of Hate 2024.

The far right of British politics is found in a wide variety of forms, ranging from now-banned organisations such as the neo-Nazi group National Action, to elements within mainstream politics.

The 2024 report by Hope Not Hate, quoted above, plots a significant advance of such movements, even in the past year, both within fringe political movements and within the Conservative Party itself, as well as in popular news outlets such as GB News.

This is seen in the shift of the Overton Window, a model used to describe the ways that what is acceptable in public speech can shift over time. In recent years the Overton Window has shifted considerably to the right, permitting many prominent individuals, not least a former Prime Minister and two consecutive Home Secretaries, to express views and use rhetoric which 20 years ago would have been unthinkable.

Far right actors who are operating within the current political system are promoting an illiberal democracy rather than the overthrow of democracy itself. In many ways, this mainstreaming of far-right discourse makes it even more threatening, because it carries a veneer of respectability, making it more electable, and more plausible to the Church.

Far right groups in this country have a variable cluster of commitments which occupy some or all of the following ideologies:

-

‘Cleaning up’ so-called ‘moral depravity’

-

Protecting the ‘Christian nation’ from the threat posed by Muslims/ multiculturalism/ the liberal elite/ [insert your own demon here]

-

Antisemitism (or sometimes, conversely, rampant Zionism)

-

White supremacy and ethnic or religious nationalism, with hostility towards migrants

-

Conspiracism around a variety of issues including climate change denial, holocaust denial, and anti-islamic conspiracy theories.

Some of these themes can be appealing to many Christians; and indeed they may intersect with what we might (depending on our own position) consider legitimate theological concerns:

-

The idea of ‘cleaning up’ the morality of society is appealing to many who mourn the national decline in ethical standards.

-

The Far Right’s commitment to ‘family values’ has links with the authentic biblical themes of fidelity and covenant love.

-

The recovery of a ‘Christian’ past in the face of the ‘threat’ posed by Muslim immigrants appeals to a fear of persecution – legitimate in some overseas contexts– and the faithful desire to see the one true God worshipped.

But while such policies or rhetoric may be welcomed by some, what many Christians may fail to appreciate is that Christian-sounding language may be cynically employed by those whose allegiance and values are quite contrary to Christian ones.

In the lead up to the 2015 General Election, the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) published what they called a ‘Christian Manifesto’, headed with the title ‘Valuing our Christian Heritage’. In its foreword, the party’s then leader Nigel Farage wrote ‘Britain needs a much more muscular defence of our Christian heritage and our Christian Constitution… Sadly, I think UKIP is the only major political party left in Britain that still cherishes our Judeo-Christian heritage.’

Nor is this sort of thing simply political posturing. In 2014, members of the political organisation ‘Britain First’ invaded mosques across the UK with army-issued Bibles. The intruders called it a ‘Christian crusade’. In the following two years, Britain First members made a habit of parading through Muslim-majority areas of several British cities, aggressively flourishing large crosses. Following a series of similar incidents, the two leaders of the organisation were jailed in 2018 for religiously aggravated harassment.

More recently, on 5 April this year, which was during Ramadan, Bristol Cathedral hosted a Grand Iftar, inviting any citizen who wished to, to join with local Muslims as they broke their fast after sunset. Large crowds gathered on College Green – just outside the cathedral – and also in the building itself. I have seen no suggestion that any act of worship was conducted. Video footage from the event simply shows people – many but not all in Muslim dress – enjoying food together, with children playing alongside their families.

Commentators immediately took to their microphones and keyboards to denounce this. One of them is an ordained priest who is a prominent ‘influencer’ with over 330,000 followers on X (formerly Twitter). He took it was a sign that we are living in the ‘Islamic Caliphate of Britain’, quoting Deuteronomy 6:14.

That particular X thread attracted more than 6,000 readers, with many people chipping in to call for ‘defence of our land’, exorcism of the cathedral, and—most disturbingly—for crusade. More tweets than I can document referred to this event as an Islamic ‘conquest’, with a number likening it to the Ottoman invasion. ‘They took over Hagia Sophia in 1453… Now they've seized the UK without firing a shot.’

The church needs to take seriously these rhetorics and acts of violence being done in its name.

Theologians Hannah Strømmen and Ulrich Schmiedel have examined the theological claims made by four different far-right groups in Europe. They offer this challenging conclusion.

"Trained theologians might not like [these] political readings of the Bible. Biblical scholars might say that they are historically implausible, that they are hermeneutically incorrect, or that they are wilfully wrong.

"But these readings are still there. The theologies that run through the far right didn’t appear out of nowhere." The Claim to Christianity, p.12.

In May 2023 the Centre for the Study of Bible and Violence gathered a group of 14 invited participants for a 24-hour consultation. They represented an international, ecumenical and inter-faith, and interdisciplinary group, with academic experts in a variety of fields, alongside those with on-the-ground experience of helping the Church respond to democratic threat by extremist groups. (This work was funded by the generous sponsorship of the British Academy.)

Our task was to consider how the UK church should respond to the rise of the radical right. The papers emerging from these discussions have been published by SCM as chapters in a book we have entitled The Church, the Far Right, and the Claim to Christianity (ed. Helen Paynter and Maria Power).

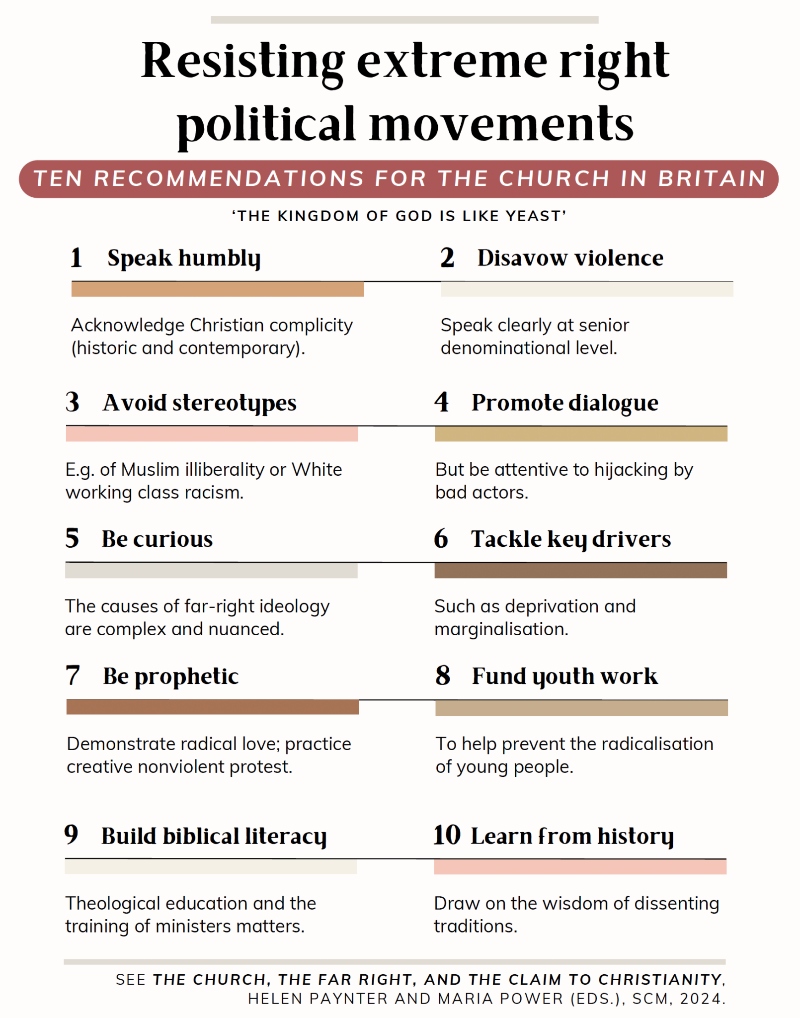

At the end of the book, I reflect on these discussions, and draw together some common themes and strands, culminating in ten concrete recommendations for the UK Church. See image below, or read here:

A series of events were held in 2024 to bring these recommendations to the attention of church and denomination leaders, and to generate discussion and conversation.

This was kicked off with a presentation made at the Senedd (Welsh Parliament) in May. You can read a report on this written by Rosa Hunt and Ed Kaneen, the co-principals of the Cardiff Baptist College here.

Keep an eye open for an event near you – or get in touch with me if you’d like to host one!

Find out more about the project and the related events here

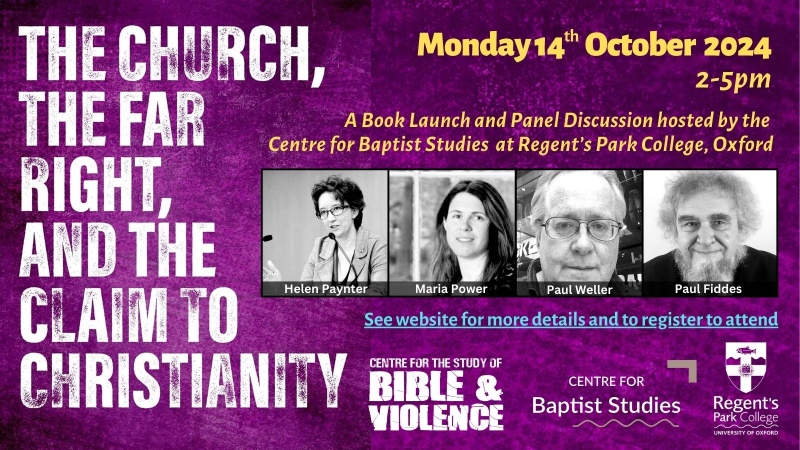

One is taking place at Regent's Park College at 2pm on 14 October. A book launch and panel with Helen along with Maria Power, Paul Weller and Paul Fiddes. Admission free. This event will look at the place of the dissenting traditions in relation to the subject of the far right and Christianity.

Helen Paynter is a Baptist minister who now serves as Tutor in Biblical Studies at Bristol Baptist College. She is author of a number of books, and the founding director of the Centre for the Study of Bible and Violence.

You can contact her here.

Do you have a view? Share your thoughts via our letters' page.

Baptist Times, 18/09/2024