Modern slavery and why we should care?

Many victims / survivors of exploitation access services from churches, writes Dan Pratt, editor of a new book exploring theologies and faith responses to modern slavery

Modern slavery now ranks as the second most profitable worldwide criminal enterprise after the illegal arms trade. There are an estimated 40.3 million people kept in modern slavery in the world today including (i):

Modern slavery now ranks as the second most profitable worldwide criminal enterprise after the illegal arms trade. There are an estimated 40.3 million people kept in modern slavery in the world today including (i):

-

10 million children

-

24.9 million people in forced labour

-

15.4 million people in forced marriage

-

4.8 million people in forced sexual exploitation

-

1 in 4 victims of modern slavery are children

Images of modern slavery and human trafficking (MSHT) often highlight sweat shops in Asia, forced prostitution in Eastern Europe, or coca farms in West Africa. For those of us in the UK, why should we care?

For several years I ministered in an emerging Baptist church in Southend-on-Sea, Essex. The church was rooted among the rough sleeping community. MSHT were not on my radar.

That was until I met Richard. Having slowing gotten to know him, he entrusted me with some of his story (ii). He had been homeless in the north-west of England. In his homeless hostel, he was offered a job paving and tarmacking driveways. In return he would be given wages, accommodation and food.

Several months after having accepted the offer, the wages didn’t materialise. He was accommodated in a run-down caravan which was sometimes shared with the owner’s dog. When he requested his wages he was threatened. He was told ‘if you try to leave, we know where your family live’. Fearing for his family and himself, Richard stayed. He was exploited for 20 years before escaping.

Richard’s story was not the only story of exploitation encountered. There was a pattern of vulnerable people being exploited in forced labour, forced sexual exploitation and forced criminality. Modern slavery is a hidden crime. Estimates of its prevalence in the United Kingdom range from 100,000 to 136,000 people being exploited (iii). Consequently, almost every community in the United Kingdom is impacted by modern slavery.

In 2015, the UK Parliament passed the Modern Slavery Act. The Act defines offences of slavery and human trafficking.

Slavery is when someone takes ownership of another person like a piece of property and often requires them to perform forced or compulsory labour (iv). This usually restricts that person’s freedom of movement and exercises power over that person’s choices.

Human trafficking is when a person arranges or facilitates the travel of a woman, man or child with a view to that person being exploited (v). The movement can be international, but also within the country from one city to another, or even just a few streets.

The extent of MSHT in the United Kingdom brings to the forefront the question of why communities and faith communities should care? The Gospels highlight the two greatest commands of loving God and loving our neighbour. Indeed, Jesus’ mission of ‘setting the captives free’ is exemplified in his early ministry. With churches and faith groups increasingly encountering victims of modern slavery, loving our neighbour and setting the captives free can become a literal act.

A Baptist colleague who ministers in a church in an affluent part of Essex writes:

Keya regularly attended our local church. She appeared shy, nervous and scared. The family she was works for dropped her off at the door and collects her exactly one hour after later. This doesn’t allow her to interact with people.

In brief conversations it becomes clear that Keya is not paid properly for her work and is not allowed out of the house without permission. The two sons in the house ridicule her. She is unable to leave because she must pay off a small debt to the family, who built her and her disabled husband a small house in India. The debt would take years to pay off.

It was a shock to those of us in the church who came to know Keya over her time with us that this situation was happening yards from our own homes. (vi)

The church had regularly welcomed a victim of modern slavery to their church services. Talking with other church ministers, it became clear these weren’t isolated cases. This led the Eastern Baptist Association (vii), with more than 170 churches in the east of England to conduct a survey among its churches relating to modern slavery and trafficking. The survey indicated that out of the 47 churches taking part, 19 per cent of them had knowingly encountered victims of modern slavery. These encounters had often been in their grassroots work or serving the community.

There will be more churches who had unknowingly served victims through their church services, food banks, crèches, night-shelters and other community activities. But why were so many victims / survivors of exploitation accessing services from churches?

The charity Hestia interviewed 12 survivors of modern slavery, who had experienced homelessness, asking them ‘where would a survivor of modern slavery who is experiencing rough sleeping go to seek help?’ Only four out of the twelve would go to the police, with one person stating they ‘… would be too scared of police’, and another, saying ‘…if they’ve been in trouble with the police before they’d be too scared’. Non out of the twelve would go to the council for help. With one person explaining they ‘…would be too scared of being deported’, and another saying, ‘…how would I know I could trust them [?]’ (viii). All interviewees indicated they would approach a church / mosque / or other religious organisation for help (ix).

In the same report, interviewees were questioned regarding what they thought were the barriers stopping survivors of exploitation who became homeless from seeking help. All indicated that ‘fear was a barrier’. Other barriers included lack of information, poor English, low self esteem, mental health, shame, mistrust, and fear of deportation (x).

Hestia concludes their report by stating that: Faith organisations and grass-roots and homelessness charities are significantly more accessible to survivors of modern slavery who are sleeping rough than existing statutory pathways (xi).

We should care because victims of slavery are some of the most oppressed individuals, who like Richard and Keya are being exploited on our doorstep and often faith communities can help safeguard them. Faith communities are often located within unique grassroots contexts. This enables victims of slavery feel able to come for help. We are in a unique position to be able to love, safeguard and walk alongside survivors of this horrendous crime. In the midst of this horrendous crime, there is an opportunity for faith communities to show and live out Christ’s love in action and to partner towards slavery-free communities.

To learn more about faith responses to modern slavery see the newly published book Slavery-Free Communities: Emerging Theologies and and Faith Responses to Modern Slavery. It includes several chapters by Baptist authors including: Paul Fiddes, Kang-San Tan, Myra Blyth, Marion Carson, Gale Richards and John Weaver. A forward is included by the Rt Hon Theresa May MP.

Dan Pratt is the Eastern Baptist Association Anti-Slavery Co-ordinator who founded and leads Together Free, the Baptist movement seeking to work with local churches to end modern slavery and human trafficking.

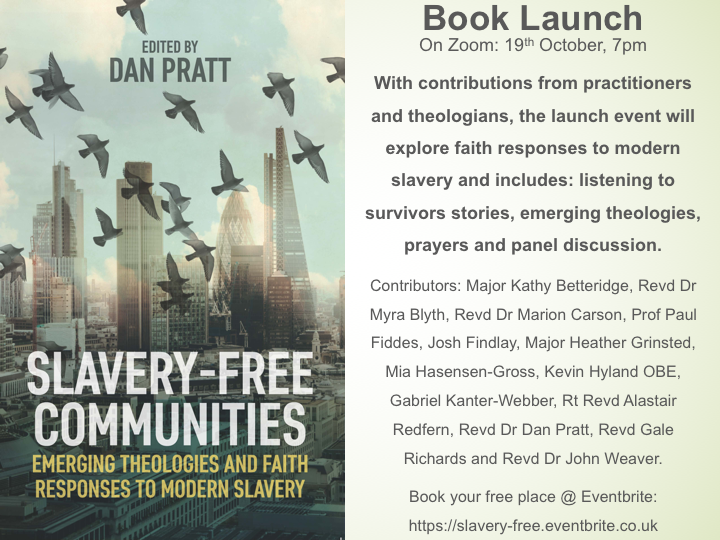

A book launch for Slavery-Free Communities: Emerging Theologies and Faith Responses to Modern Slavery takes place on Zoom: 19th October, 7pm.

A book launch for Slavery-Free Communities: Emerging Theologies and Faith Responses to Modern Slavery takes place on Zoom: 19th October, 7pm.

The online event will explore faith responses to modern slavery and includes: listening to survivor’s stories, emerging theologies, prayers and panel discussion.

Contributors: Major Kathy Betteridge, Revd Dr Myra Blyth, Revd Dr Marion Carson, Prof Paul Fiddes, Josh Findlay, Major Heather Grinsted, Mia Hasensen-Gross, Kevin Hyland OBE, Gabriel Kanter-Webber, Rt Revd Alastair Redfern, Revd Dr Dan Pratt, Revd Gale Richards and Revd Dr John Weaver.

Book your free place via Eventbrite: slavery-free.eventbrite.co.uk

Slavery-Free Communities: Emerging Theologies and Faith Responses to Modern Slavery can be bought from our online shop here.

[i] Alliance 8.7, 2017 Global Estimates, available from https://www.alliance87.org/2017ge/modernslavery.html#!section=0, accessed 29.01.21

[ii] Richard’s name has been changed and the story is shared with permission.

[iii] Gren-Jardan, T., 2020, It Still Happens Here: Fighting UK Slavery in the 2020s, London: Justice and Care, available from www.justiceandcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Justice-and-Care-Centre-for-Social-Justice-It-Still-Happens-Here.pdf, accessed 14.10.2020

[iv]Minderoo Foundation, 2018, ‘More than 136,000 people are living in modern slavery in the United Kingdom’, Walk Free Global Slavery Index, 18 July, available from www.globalslaveryindex.org/news/more-than-136000-people-are-living-in-modern-slavery-in-the-united-kingdom/, accessed 14.10.2020

[v] Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2018, Article 4: Freedom from slavery and forced labour, available from, www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/human-rights-act/article-4-freedom-slavery-and-forced-labour, accessed 29.10.2020

[vi] Modern Slavery Act, 2015, p. 2, available from, http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/30/pdfs/ukpga_20150030_en.pdf, accessed 29.01.21

[vii] Name has been changed. With thanks to Revd David Mayne, and Shoeburyness and Thorpe Bay Baptist Church for sharing this story.

[viii] Eastern Baptist Association, refer to www.easternbaptist.org.uk

[ix] Hestia, 2019, p10, Underground Lives: Homelessness and Modern Slavery in London, October 2019, available from, www.hestia.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=7c01ce39-fded-468f-bca3-6163ed16844e, accessed 22. 02. 21

[x] Hestia, 2019, pp10-11

[xi] Hestial, 2019, p10

[xii] Hestia, 2019, p14

Baptist Times, 04/10/2021