Understanding today’s refugee children through the Kindertransport

Rescue brings its own culture and identity challenges, which are explored in a new novel set in post-war Britain. By Bobbie Ann Cole

In recent years, tens of thousands of unaccompanied child refugees have arrived in Europe, confused, vulnerable and fleeing desperate situations. What will life be like for them and how can we understand their struggles? The Kindertransport of the 1930s might provide and answer…

In recent years, tens of thousands of unaccompanied child refugees have arrived in Europe, confused, vulnerable and fleeing desperate situations. What will life be like for them and how can we understand their struggles? The Kindertransport of the 1930s might provide and answer…

Eighty years ago, ten thousand Jewish children were invited to live in Britain on temporary visas in an operation known as the Kindertransport, or ‘Transport of Children’. The catalyst for the British government’s invitation was Kristallnacht, the Night of the Broken Glass, on 6 November 1938. Jews in Germany and its surrounding nations endured four successive nights of terror during which synagogues were desecrated and torched, Jewish cemeteries and shops smashed up and Jews dragged from their beds to be beaten or executed.

Soon afterwards, a call went out on the Home Service on British radio: the government was seeking foster parents for the Jewish children who would be arriving by boat and train. No heed was paid to supporting the cultural or faith backgrounds of these children. They landed where they landed. Some would have good experiences, others not so good. The transports continued until war was declared against Germany, in September 1939.

The children were all supposed to return to their families when it was over, but this would prove impossible, for millions of Jews had perished in the Holocaust. Those children who were reunited with their families had lived apart from them for seven years or more. During that time, they had gone through a huge cultural and linguistic shift.

The rift was underscored by the vast difference in wartime experiences between Jewish survivors, who had spent furtive years in hiding or as prisoners in the death camps, and their children, who had remained relatively safe in Britain through the war.

The parents’ experiences were beyond the comprehension of their children. It became widely understood in the nascent State of Israel that Holocaust survivors, though guilty of nothing, were ashamed to talk of what had been done to them and would wave away questions that revived painful memories. A wall of silence went up that often proved impossible to break down.

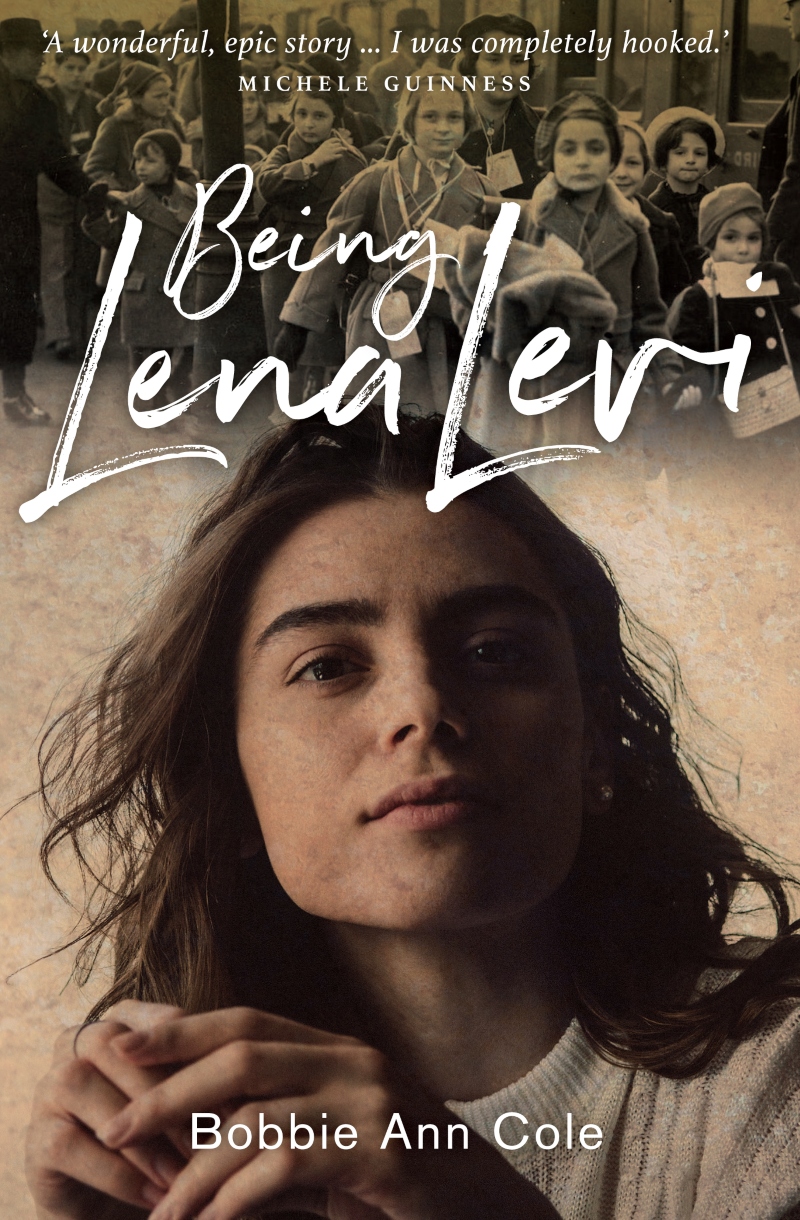

The heroine of my recently published novel, Being Lena Levi, is a Kindertransport child but is too young to remember, and her foster mother hasn’t let on. Although the minimum age was supposed to be five, parents of the very young (and also those who were officially too old) cheated. She was just three in June 1939 when she was brought to England on a boat from Bremen. An older cousin was supposed to chaperone her, but she got last-minute cold feet and remained in Germany, leaving Lena to travel alone. That cousin would die in Auschwitz.

It is 1950 and Lena is nearly 15 when, out of the blue, a young, exotic and beautiful – but terribly damaged – birth mother shows up to claim her daughter. Mutti is a Holocaust survivor, now living on a kibbutz in the newly formed State of Israel. Can Lena, who considers herself ‘properly English’, step into the shoes of a former self she hardly remembers? Does she even want to? The discovery that she is Jewish raises many questions for this Sunday Christian as she instinctively discerns that what she believes will be a vital element in her quest for her true identity.

This fiction that could be true was inspired by the Bible story in 1 Kings 3 two of two women who claim the same baby. They appear before King Solomon, asking him to choose between them. He calls for his sword and is about to cut the baby in two and give each half, when one mother steps forward to say she will give the baby up and let the other mother have her. Solomon deems her to be the true mother and gives her the child.

This account raises a lot of ‘what ifs’ for me. What if the child has ended up with the ‘wrong’ mother? What if the foster mother were a better mother than the birth mother? How would a child feel if they didn’t know and then found out? Does nature trump nurture? And what does it take for a mother to give up a child?

The result is Being Lena Levi, set in 1950 Canterbury, with its bombsites that sprout purple buddleia bushes, and the newly formed State of Israel, under threat from nations on all sides that would annihilate it.

My characters are:

-

a feisty girl who thinks she always knows her own mind.

-

Mutti – her birth mother – who has gone from the barbed wire that contained her in a concentration camp to the barbed wire of a displaced persons’ camp and now the barbed wire that keeps Israel’s enemies out.

-

And Mum, who finds it almost impossible to show her feelings. They are, truly, a love triangle, one that gives insights into the multiple conflicting loyalties and questions of identity that thousands of young people, freshly arrived in Europe from all parts of Africa, central Asia and the Middle East, will be asking over the coming decades.

Bobbie Ann Cole is the author of Being Lena Levi, published in September 2019 by Instant Apostle (978-1-912726-09-7, RRP £8.99), available in Christian bookshops and online.

Do you have a view? Share your thoughts via our letters' page.

Baptist Times, 24/10/2019