How black majority churches are redefining the UK's religious landscape

Nationally, there is a decline in church attendance and growth across most denominations. But black majority churches are growing significantly. Why?

And how can other churches learn from them? By listening and reconnecting, writes David Shosanya

Once a year I am invited to Spurgeon’s Bible College to deliver a lecture on mission in a Black Majority Church Context. There is always a sense of expectation as students wait in anticipation of what is about to be said. The majority of students are open and curious. Inevitably, a few students are less certain and consequently not fully at ease with the subject matter.

However, the students are sufficiently cognisant of the fact that there must be explainable reasons for the exponential growth of churches that are disproportionately populated with Christians of African and Caribbean Heritage (my preferred description).

Generating heat

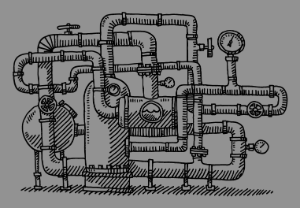

The lecture usually starts with an analogy that I believe captures the current need for co-operation between white British Christians and sisters and brothers from an African and Caribbean heritage. It goes like this: African and Caribbean heritage churches/Christians can be likened to a state-of-the-art boiler that has the inherent capacity to generate and distribute significant amounts of heat without much effort.

I then suggest that the problem with the boiler is that it is disconnected from the radiation system that has the capacity to carry the energy from the boiler throughout the house and consequently raise the overall temperature.

I then suggest that the problem with the boiler is that it is disconnected from the radiation system that has the capacity to carry the energy from the boiler throughout the house and consequently raise the overall temperature.

I then offer the following thought: African and Caribbean heritage Christians come with and offer a tremendous capacity for spirituality, prayerfulness and a strategic focus on mission.

However, the challenge they face is that the energy they generate through these God-given disciplines and gifts is often not able to be translated into meaningful connections with indigenous communities.

As a result, in the majority of cases, they are not seeing individuals from white communities come to faith.

If they do they tend not to remain in their churches. The goal of ecumenical and other inter-church initiatives, I suggest to students, is to connect the efficiency of the boiler to generate heat with the effectiveness of the radiation system to distribute it.

Usually the penny drops at this point and the students are able to perceive the missional imperative of ecumenical relations and proceed with a dialogical disposition. This point is important and should be noted: there is often an unconscious – but nevertheless very real – sense of dis-ease that colours the lenses through which the subject matter is viewed.

Need for dialogue

This is not a phenomena that is unique and particular to students. I recollect being invited, along with other leaders, to the home of a leading figure in the British Christian church scene.

A conversation was initiated: an exploration about leadership, mission, African and Caribbean Christians reaching white communities and why white people do not seem able to serve under black leadership. It was a cordial discussion with each person respectfully offering their unique perspectives on the range of dynamics at play.

After a short while a white leader assumed a culturally superior disposition and proceeded to prescribe what steps needed to be taken if African and Caribbean heritage churches and their leaders were to be able to exercise leadership over and be relevant, missionally and otherwise, to white Christian communities. His comments were valid but the spirit in which he spoke was less welcomed.

There was an awkward silence – one that black people are used to! We know the silent code which says? “Let him speak because he thinks that we have got no insights of our own to offer.”

So we did, while at the same time as a matter of courtesy offering perfunctory comments to prevent the conversation from stalling. I make this point to highlight the need for genuine dialogue around this issue; a dialogue that is multi-voiced.

I have reflected extensively and asked the opinions of many fellow African and Caribbean leaders on why white individuals find it difficult to either join African and Caribbean heritage churches or sit under their leadership. I have concluded that three assumptions – superiority, inadequacy, incompetency – make this problematic and will need to be challenged and addressed if there is to be a change.

Trying to reach white communities

In 2009 I undertook some research as part of my sabbatical study and sought to identify and understand what steps African and Caribbean heritage churches were taking to reach white indigenous communities with the Gospel.

A number of themes emerged: firstly, the church leaders I spoke with had made significant attempts to modify their styles of worship to be more appealing to white individuals; secondly, they had taken on board comments an about their style(s) of preaching and its incompatibility to the indigenous population; thirdly, they had explored different forms of prayer that might more easily resonate with white communities.

A number of themes emerged: firstly, the church leaders I spoke with had made significant attempts to modify their styles of worship to be more appealing to white individuals; secondly, they had taken on board comments an about their style(s) of preaching and its incompatibility to the indigenous population; thirdly, they had explored different forms of prayer that might more easily resonate with white communities.

In some cases there were severe setbacks resulting from these modifications.

Perhaps the most significant setback was that in making the required adjustments, in an attempt to be open to white British communities, African and Caribbean heritage churches/leaders inadvertently compromised the integrity and efficacy of their own religious traditions, especially the capacity faith had to serve as a wall of resistance against their experiences of racism, to the extent that they no longer adequately met the felt needs of their own members.

This, in a very real sense, is the critical tipping point between African and Caribbean heritage churches self-identifying as a ‘reverse mission movement’.

They grasp the very real implications of the need to genuinely and sacrificially incarnate in a manner that is contextually relevant to white communities.

Why black churches are growing

Despite the very real up-hill challenges that African and Caribbean heritage churches face, they are experiencing significant growth. I want to offer five reasons for such growth:

-

Prayer. African and Caribbean heritage churches are, by-and-large, devoted to the ministry of prayer. It is not unusual for them to be involved in 7, 10, 14, 21, 30 or 40 day fasts in preparation for mission or in consecration to God.

-

Proclamation. Preaching the Word – whether from the pulpit or on the streets – constitutes a foundational part of their DNA. Closely related to the act of preaching is an unshakeable confidence in scripture as the ‘Word of God’ and its ability to change lives and communities for the better.

-

Power. African and Caribbean heritage churches take seriously the interplay between the spiritual and temporal realm. The reality of principalities and powers and the demonic is very much a feature of their world-view/spirituality. They are intentional in articulating their viewpoint as well as standing with Christ against the powers/demonic even in the face of intellectual snobbery that can reduce such perspectives to primitive thinking.

-

Strategy. There is sometimes a caricature that African and Caribbean heritage churches are chaotic. This prejudice can often prevent external observers from recognising the strategic dimensions of their mission and ministry. It is not unusual for a single African and Caribbean heritage church to have a vision to reach a city or a nation and to have mapped out a plan to realise that vision.

-

Social Action. Increasingly African and Caribbean heritage churches are engaging in practical acts of kindness to demonstrate God’s love and as a means of connecting the boiler to the radiation system.

These churches are growing significantly and redefining the religious landscape of the nation. They are being intentional in creating environments where people from all cultures feel welcomed and affirmed.

There are challenges of their own that they are negotiating. However, they are unequivocally committed to being salt and light and seeing God’s kingdom come in the UK. You can help by developing a partnership with an African and Caribbean heritage church near you – connect the boiler to the radiation system! Blessings.

David Shosanya is London Baptist Association’s Regional Minister responsible for Mission

Pictures:

Choir - HOPE Together

Boiler - Frank Ramspott

GreenLaneBaptist Church- The Express & Star, Wolverhampton

Baptists Together, 25/04/2015